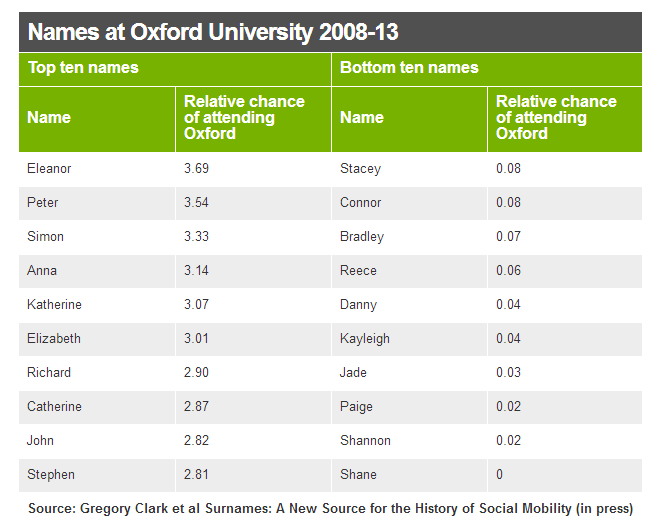

It isn't that the name itself is particularly powerful, or destructive; rather, the sorts of people who wind up naming their daughters Eleanor are very different, on average, from the sorts of people who wind up naming their daughters Kayleigh. From the BBC piece:

However, there is no evidence that it's the names causing such a marked discrepancy, rather than other factors they represent, Clark says. Different names are popular among different social classes, and these groups have different opportunities and goals.Our baby-naming algorithm, which wound up choosing Eleanor for our girl, started with a domain of names in the top 1000 from 1880 to 1930 in the US, then eliminated any names that were in the top-100 any time in the last three decades. So you rule out the made up stuff while also ruling out having too many classmates with the same name. But we're the kind of people who would choose that kind of algorithm.

"That's something that's emerged in modern England that didn't exist around 1800," he says. When he re-ran his study, but this time looking at students attending Oxford and Cambridge in the early 19th Century, he found the correlation between names and university attendance far less marked. First names simply weren't the social signifiers they are now.

What's happened since then is a move towards unusual, even unique, names. Before 1800, Clark says, four first names referred to half of all English men. In 2012, according to the Office for National Statistics, the top four names (Harry, Oliver, Jack, Charlie) accounted for just 7% of English baby boys (and the picture was much the same in Wales).

Similarly in the US, in 1950, 5% of US parents chose a name for their child that wasn't in the top 1,000 names. In 2012, that figure was up to 27%.

As late as the 18th Century, it wasn't uncommon for parents to call multiple children the same name - two Johns for different grandfathers, for example. Now parents increasingly look for unique names or spellings of names. As Jean Twenge points out in her book the Narcissism Epidemic, Jasmine now rubs shoulders in naming lists with Jazmine, Jazmyne, Jazzmin, Jazzmine, Jasmina, Jazmyn, Jasmin, and Jasmyn.

I especially liked the BBC piece's pointing to Figlio's work on names. It's pretty common for researchers to use audit studies to test for racial discrimination: they send out otherwise-equivalent vitae, but put a 'black-sounding' name on some and a neutral one on others. They tend to find a penalty for having a black-sounding name. The problem with these kinds of studies is that they simultaneously test for black-sounding and for class-linked names: instead of testing black versus white, they're effectively testing lower-class versus upper-class names. Here's Figlio:

This paper investigates the question of whether teachers treat children differentially on the basis of factors other than observed ability, and whether this differential treatment in turn translates into differences in student outcomes. I suggest that teachers may use a child's name as a signal of unobserved parental contributions to that child's education, and expect less from children with names that "sound" like they were given by uneducated parents. These names, empirically, are given most frequently by Blacks, but they are also given by White and Hispanic parents as well. I utilize a detailed dataset from a large Florida school district to directly test the hypothesis that teachers and school administrators expect less on average of children with names associated with low socio-economic status, and these diminished expectations in turn lead to reduced student cognitive performance. Comparing pairs of siblings, I find that teachers tend to treat children differently depending on their names, and that these same patterns apparently translate into large differences in test scores.I wish that audit studies instead used a cross-cutting method that would test Da'Quan against Dwayne and Cleetus instead of just against Peter. Put it into a 2x2 matrix with race on one axis and class on the other.

First names may just be signals, but "just signalling" hardly means unimportant. If you're economising on time while going through the resumes or university applications, and if a Cleetus is less likely than a Peter to know which fork to use at the important dinner with a client or donor, well, a Cleetus would have to be better than a Peter to get a second look. Because parents who have some minimal social capital expect this to be at least somewhat likely to be true, they make different naming choices than those who don't.

Colby Cosh is right:

The parents who need Crampton’s naming algorithm most will give up long before they hit “Borda count”.

— Colby Cosh (@colbycosh) April 14, 2014

The separating equilibrium separates.

I'd tell you to avoid giving your kids dumb names, but if you're reading this, you almost certainly already know it.

* I really need to get his book. The interview teasers have been very tempting.

Previously:

Time discounting, Lemmus. True today. True of any of her cohort when she turns 13? Doubtful. Eleanor Rigby was released in 1966. When Eleanor's 10, in 2020, that'll be 54 years in the past. I was born in '76. Ought my parents have worried about songs written in 1932?

ReplyDeleteOur naming algorithm for Elizabeth wasn't as, err, rigorous as yours, but we most definitely stayed away from "dumb" names. I doubt our Elizabeth will attend an Oxbridge university, but should the opportunity arise I'd certainly encourage her to do so. Interestingly one of the names in the mix for #2 is Catherine, which I guess says something about us. I am steering away from it though, mainly because there will be a lot of them soon due to the popularity of a certain English aristocrat currently touring New Zealand. However, we will not be choosing Kayleigh instead.

ReplyDeleteAh, but don't they teach you anything in those fat textbooks? Of course you need to apply the Beatles-specific discount rate! Scholars disagree about the exact denominator, but roughly, you need to divide the number of years by a factor of four.

ReplyDeleteYour parents should have worried about songs written in 1932 written by the Beatles. Lucky them!

From the BBC link: 'Conley, who is a sociologist at New York University, says that children with unusual names may learn impulse control because they may be teased or get used to people asking about their names.'

ReplyDeleteAnd all I can think of is A Boy Named Sue.

Nah, they were worried about the Gershwin discount rate; we picked Ira anyway.

ReplyDelete